East Lake Meadows

3/24/2020 | 1h 45m 56sVideo has Closed Captions

The story of a public housing community raises critical questions about race and poverty.

Learn the history of East Lake Meadows, a former public housing community in Atlanta. Stories from residents reveal hardship and resilience, and raise critical questions about race, poverty, and who is deserving of public assistance.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

East Lake Meadows

3/24/2020 | 1h 45m 56sVideo has Closed Captions

Learn the history of East Lake Meadows, a former public housing community in Atlanta. Stories from residents reveal hardship and resilience, and raise critical questions about race, poverty, and who is deserving of public assistance.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch East Lake Meadows

East Lake Meadows is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

PARKS: When we moved to East Lake Meadows, that was just like Heaven to us.

(sirens) Until it became a nightmare.

BLACKMON: This previously all white part of Atlanta known as "East Lake" became available for African Americans to move in.

RESIDENT: Well, I hate to leave, but I don't want to be the only white family living here.

LIGHTFOOT: I figured they were gonna be fine because they were brand new.

After a couple a years, they were not okay.

REPORTER: Residents remember when it was a safe place to live, but now they fear for their lives.

RESIDENT: People just livin here on borrowed time.

VALE: Public housing has always been both a financial proposition and a moral one about which people both need it and somehow deserve it.

ALLEN: We were all saying they needed to do something about this place...

They did something, all right.

HANNAH-JONES: I don't think we ever gave enough credit to people who worked very hard to build a place for themselves.

There was no one else who was going to be there.

PARKS: Even in poverty, there's always that beacon of light.

NARRATOR: Funding for "East Lake Meadows" was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

And by the generous contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

(birds chirping) (dog barking).

(children playing and laughing) (sirens) ♪ ♪ BURSON: Standing with your back towards Glenwood and looking forward towards East Lake Meadows it looks like a military installation, you know the way it was laid out like Fort Bragg or Camp Lejeune, because you just had rows of apartments just as far as the eye could see.

Some of the land was flat and as it went on it dipped and then it came back up, and you had apartments on the hill and it was just vast.

It was, it was a lot of concrete.

PARKS: When we moved to East Lake Meadows that was just like heaven to us.

We went from no food and no heat and five to a room, to bedrooms where you can go wash your clothes, everything in the house, you were warm, so we were just happy there until it became a nightmare.

ANCHOR: Residents say that drug dealers are all over East Lake Meadows.

WOMAN: You hear the gunshots going off all the time.

All you can do is grab your kids up.

DAVIS: We want a community center, we want some social services programs out there.

BLACKMON: It was just this chaos.

It was called "Little Vietnam" by the police for good reason.

It was just viewed as irredeemable.

It was just it was a place that was beyond the capacity that anybody could imagine things being different.

ALLEN: We were all saying that, "“They need to do something about this place.

They need to fix it up or do something.

"” They did something all right.

PHYLLIS: There used to be a lot of, um, bad things in our neighborhood.

Now they are, now, now they are tearing down the buildings and they are going to build them into new buildings and some of the people won't be back so we will have a good community where people can have their children out and playing.

ANTHONY: Is you going to live over here when they fix the houses up?

PHYLLIS: Um, I don't think so.

GOETZ: We can agree that East Lake Meadows was a terrible place.

and we can then even agree that demolition was necessary but if our first concern was the residents of East Lake Meadows, then the way we would have gone about it and the outcome would have been different.

BURSON: They promised families that they would be able to come back in life would be better.

It didn't happen that way.

PRATTILLO: Over the long decades of housing policy in this country, we have at some time said, yes, we have a responsibility to house people.

A responsibility to give decent, safe, affordable housing.

It's a basic human need.

And so sometimes we've said of course we have that responsibility, and then at other times we completely turn our back on that responsibility.

VALE: Public housing has always been both a financial proposition and a moral one... about finding not just need but somehow measuring worth.

How do we begin to sort out which of the many people who could be assisted, both need it and, and somehow deserve it.

It becomes a window into race relations; it's a window into understanding the role of home ownership in society.

And it's a way of understanding the level of compassion there is for those who do need some assistance.

COBB: We are not mature enough as a society I think to look in the mirror and see how we manufactured American poverty.

How we manufactured housing that was, uh, meant to seclude these poor people.

Uh, and how we turned a blind eye to creating, to creating a middle class while simultaneously excluding people from it.

["“Little Brown Jug"” Glenn Miller & His Orchestra].

MAN: Uncle Sam starts clearing Atlanta slums in the plan to give modern dwellings to the poor.

Secretary of the Interior Ickes fires the first blast.

(explosion) ROSENSTEIN: We think of public housing as a place where low income, mostly minority families live, that's not how public housing began in this country.

During the depression, many, many families lost their homes, they couldn't afford to pay rent, and so there's an enormous housing crisis in the country, that was the reason that the Roosevelt administration began the first public housing for civilians in the nation's history.

FDR: Here at the request of the citizens of Atlanta, we have cleaned up nine square blocks of antiquated, squalid buildings.

And in their place, we see the bright cheerful buildings of the Techwood housing project.

ROSENSTEIN: The Public Works Administration began to build public housing across the country primarily for white middle class families.

It also built some housing for African-Americans, but it was always segregated, separate projects for whites, separate projects for African-Americans very often creating segregation in neighborhoods, or communities that had not known segregation, before.

VALE: The government had no interest in seeing this kind of housing go to the poorest of the poor.

The poorest of the poor were the people they were trying to get out of the slums to make way for the upwardly mobile working class.

SCHANK: They want residents who fit a certain image...

They present them as a middle-class population.

you'll see a mother in the starched dress and the perfect white apron in her kitchen with her appliances.

They're telling everyone these people are low-income, but they're the deserving poor.

And deserving poor means you fit into this middle-class image of respectability.

MAN: Cities within cities, scientifically planned and built where a man and his family with a small income can live with comfort and dignity.

PATTILLO: The government thought about public housing as a step up for families.

you're working hard so you're able to save, and hopefully you know you live in public housing one or two years and you will then be able to move into your next step.

the next step for whites was very clearly a house in the suburbs which was supported through the federal government's um, insuring of home mortgages.

HANNAH-JONES: When the government's deciding which loan it's going to insure and which loans it doesn't it explicitly looks at race neighborhoods that are white will get the highest rating are most insurable.

integrated neighborhoods will be less desirable; and often the least desirable of all neighborhoods are gonna be black neighborhoods.

And so the government literally takes maps of every city and it outlines black neighborhoods in red.

So from the 1930's until the 1960's 98% of all federally subsidized loans go to white Americans.

That means that white Americans are getting into houses; they're able to build wealth; and black Americans are largely shut out of that market or having to finance through other means.

KRUSE: The suburbs are wholly a creation really of the federal government.

the government enables the movement out into the suburbs through the rise of new infrastructure.

The interstate highway system started in 1956, is a huge boom that helps make suburban living possible.

In many cities across the country, they put those highways there, in some cases, to erase what were regarded as black slums, uh, but always to try to keep white and black communities apart.

PATTILLO: So, white families who had been living in public housing.

They now had the support of the federal government to buy a home.

Whereas there was no next step for black public housing residents.

There was no ladder.

ROSENSTEIN: So, the public housing that originally had been intended primarily for white families, became really the anchor of many urban neighborhoods that became all black.

VALE: Increasingly across the country the waiting lists for public housing turned towards.

More lower income households, and so in Atlanta and in other cities the housing authorities went with those who applied.

So this was a major transformation, to really see public housing become the battlefield hospitals.

the place where you cope with the poorest of the poor and not reward the best off among the poor.

COBB: The cumulative effect of all of this is that you wind up with, two entirely different relationships to this country.

one is the lineage of the New Deal, through post World War II, through the reforms in the economy, you know, suburbanization and housing that has created, you know, this ideal, you know, in America.

And the other, is a population that has by and large been denied access to those things.

["“Torquay"” The Fireballs].

NAUGHTON: The original East Lake neighborhood was a place where the wealthy from Atlanta moved out during the summer to get away from the heat of the city.

And there was a little lake there called East Lake and it ultimately became the site of the East Lake Golf Club.

(crowd cheering).

NAUGHTON: It was the place where Bobby Jones learned to play golf.

BLACKMON: At the beginning of the 1960s, East Lake was this middle class and upper middle class white area of the city, exclusively white.

I think the numbers are if you go back and look at the 1960 census there were eight thousand white residents and nine African Americans those African Americans would have been maids or other people who lived on the property of a white person.

KRUSE: African-Americans are chronically overcrowded in this central part of the city, but they couldn't find space anywhere else.

They weren't able to buy homes in white neighborhoods across town because of the prevalence of what were known as restrictive covenants.

These were lines written into the deeds of homes that forbade the, uh, purchase or occupancy by non-whites.

So when the Supreme Court strikes down the enforcement of restrictive covenants essentially rendering them useless.

it's open for African-Americans to move into previously white neighborhoods.

ALDERMAN: There has been some talk in the plan that there would be a more or less exchange for the citizens of the white community to ah, give way to certain land to be used by citizens of the negro community.

BLACKMON: The black population in the city was surging, and one of the big compromises that developed was essentially an, ah, an arrangement that areas of the city where African Americans had been prohibited from living would be opened up.

Blacks could begin moving into these neighborhoods, ah, in and in return they would not move into certain other neighborhoods that whites still weren't ready to leave.

And one of the results of that was that this previously all-white, somewhat affluent but beginning to age part of the city known as East Lake, ah, suddenly became available, ah, for African Americans to move in.

["“Going it Alone"” Doug Wamble].

LIGHTFOOT: My Aunt Gladys bought a home and she had moved.

And in your mind, in your heart, you gonna hope and pray and say, "I sure hope that all the white people don't move out the neighborhood just because we're moving here.

We couldn't be that bad."

Next thing I know, there was for sale signs everywhere, everywhere.

I want to say they gave away the community sort of, you know.

Call it white flight.

She said, "the week after I moved in my house, three white people put their homes up for sale."

They were pretty much giving away those houses.

WOMAN: I hate to leave, really.

But uh, I feel like that I am out of place, you know living in this community.

REPORTER: Do you feel that your attitude can be changed to make you want to stay here and live among blacks?

WOMAN: Well, I, I don't know.

I mean I'm not, uh, prejudice.

Uh, I just as soon, you know, to live here is to live anywhere else, but I don't want to be the only white family living here, you see what I mean?

KRUSE: Whites had been led to believe that African-Americans moving into their neighborhood would destroy their property values, their real estate agents, local banks, local politicians, everyone told them that if blacks move into your neighborhood your property values will crumble.

LIGHTFOOT: They tried to move as far as they could from us.

they had a lot of places to go.

We didn't have a lot of places to go.

BLACKMON: It was a reflection of a classic apartheid American city.

By the end of the decade, East Lake had gone from having eight thousand whites and maybe nine black people to nine thousand blacks and about a thousand white people.

and so it was as dramatic a reversal in terms of the racial composition of the neighborhood as could possibly occur.

NAUGHTON: Members of the East Lake Golf Club were doing what a lot of other wealthy white folks were doing in Atlanta and that was fleeing the city.

And so the membership of that Club sold what was called the number two course, their second golf course to the Atlanta Housing Authority for a new housing project.

RESIDENT: If you zone this beautiful golf course for these cheap apartments, What are you gentleman going to do with the rest of us out there?

Who wants to live in a section where there are 1600 cheap apartments?

The people of Atlanta are fleeing to Dekalb county where we get a little more protection.

["“Jim Crow"” Wynton Marsalis].

BLACKMON: And so they sell this thing off.

And a big giant many hundreds of units housing project is built on the site right next to, twenty feet away, from what was once the most historic, elite, ah, exclusive, country club in Atlanta.

NAUGHTON: East Lake Meadows was built in 1969 and 1970. it was one of the last public housing communities built in that era in Atlanta, and it was as far away from mainstream Atlanta as you could be and still be in the city I think East Lake Meadows was built exactly the way it was planned in terms of wanting to create a place where we could push the least of these and forget about them.

["“Fast Blues in A"” Rev.

Gary Davis].

MARSHALL: I was born in Lincolnton, Georgia.

June the 10th, 1946.

My father sharecropped.

They had cotton.

They had corn, peanuts.

all types of vegetables, I used to thought we were rich until I got older, and then I knew we were just living from day to day.

We moved in '71 to East Lake Meadows.

My husband, he moved here.

then he sent and got me and my two daughters I thought it was real nice area to live in.

In '72, my husband passed, I had four childrens and I was pregnant with my baby, I had to take care of, the household and all of that then so, I just did what I had to do.

So I just stayed.

PARKS: We lived in a house.

right here in the center of Atlanta.

I know most people would think that we lived in some third world country, but we really didn't.

It was so many of us that we took turns sleeping in a bed.

My mother could not afford a lot of heat, so what we would do is the living room was, uh, sectioned off from the middle room.

and all of the children huddled there.

But, like if we walked into the living room, you could actually blow your breath and you could see the frost.

We moved into East Lake around, November of 1970.

And my mother was paying, basically, $45 for everything.

We had actually three or four bedrooms, which we had never experienced that.

So when you come from an environment of no food, no heat, cold, to a housing project, that was just like heaven to us.

LIGHTFOOT: I was playing basketball one day and somebody rode by who knew me and said, "Hey man, your house on fire."

I said, "Man, you kidding."

"No, your house on fire."

So I caught a ride, went up there and the house was on fire.

ELGIN: Well we had a drop wire over the house and somehow it dropped down and hit the house.

Somebody called the fire department and they were putting it out when we got there but it was too late.

LIGHTFOOT: After the fire, they were going to try to separate us in the, uh foster care system.

my mom told them "No way.

You know, you'll have to kill me.

No way."

I don't even like to think about it, but that made me really close to her.

That made us really tight.

When I think about how hard she fought to keep us together.

BARBARA: We moved to East Lake Meadows in 1971.

It was helpful because we lost so much in the fire that it was a good place for us to start over.

It was only a few residents over there.

Maybe 20 people living there in East Lake Meadows so we started out from the very beginning.

LIGHTFOOT: My impression were they were going to be fine because they were brand new, you know.

No reputation, They were not even filled up so you know, I figured you know, they was going to be okay.

But I found out after a couple years, they were not okay.

DAVIS: So, by the mayor coming out here ain't gonna do anything because housing's already doing what they promised to do back...

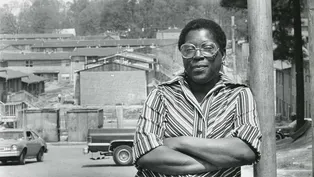

PARKS: You could not speak of East Lake Meadows without speaking of Eva Davis.

She was a spitfire.

She, she really did a lot in that neighborhood.

DAVIS: I've been doing the job that the welfare department should have been doing for the residents of East Lake Meadows.

I've been getting clothes for the people, I've been using my personal money to help people with food in my community.

I have been using my personal money to help organize a little league baseball team so I really don't feel like I owe them anything.

And by the way... EL-AMIN: Miss Davis was a feisty, young old lady and that's what I loved about her.

She didn't play some people loved her, some people didn't.

but she was for the right things.

She helped anybody that needed her help and even some that wouldn't come to her and ask for help, she would offer help.

She didn't bite her tongue for anybody, she was just real, one hundred, with everybody.

DAVIS: I grew up on a farm in Crawfordville, Georgia, Taliaferro County.

And it was a country place and I, it was way down in the woods.

but there was no jobs down in our hometown, none more than the cotton field and I got tired of the fields.

So I moved to Atlanta.

LONGINO: She met my grandfather and, Shortly after she got to Atlanta the relationship apparently you know didn't work so she was a single mom at that point with eight kids.

HEATH: In June, of '71.

we moved to East Lake.

And I said, "Wow, we're in the middle of nowhere!"

Nothing was out there but those apartments.

But they were very pretty and roomy inside.

I really loved it.

LONGINO: She decided as the families began to move in she would introduce herself, go door-to-door, just talk to people.

She never met a stranger.

She was all for making sure everybody benefited from the situation and making the best of a situation.

BLACKMON: Early on in East Lake Meadows they formed an association of tenants and she was elected the first president of the tenant's association, and if you wanted to do anything in the vicinity of that housing project or inside it, you got the message that you really needed to talk to Eva Davis before you did anything.

DAVIS: For number one sir, they got, they go to visit the welfare recipients without giving them a written notice or even a call.

NAUGHTON: You could watch her insert herself in between people and the public systems that were supposed to be serving them.

If Ms. Davis liked you if you were falling in line with Ms. Davis, she would pick up the phone then and call the Housing Authority and make sure somebody got out here and fixed your toilet.

And Ms. Davis would be a bulldog to make sure that that really happened.

MOORE: You know, we could have a broke water heater.

If we go call Ms. Eva Davis, say, "Look, Ms. Eva Davis, my heater's been broke two or three weeks and these folks ain't come up here and fixed it yet."

After you talk to her, in two or three hours, or less, somebody's there to fix your water heater.

Politics didn't care about us.

They didn't care.

We had to have people like Eva Davis, To demand certain things to be done.

ELGIN: They used to have a Revival Tents that would come in periodically to save us.

they figured you were, like, the demon child, you were devils and the reason you were poor because you probably were sinning against God.

they'd have an organ player playing and he would preach a word and then he would line people up that were so-called '‘possessed' with the demon.

he'd put their hand over their head and they would tremble, and they would fall and they would spit up what he called the demon coming out.

And then they would ask for their donations and people would give their money.

They would always go to one project after another with their little Revival and if they feel we weren't saved enough they would come back and save some more.

Even as a kid I thought that was crazy but they did, they did a lot of that.

Because they thought we needed it.

LIGHTFOOT: Whoever designed the apartments, they did a very poor job landscaping.

And if you look at some of the earlier pictures when they first transplanted the grass or seeds or whatever, it's very green.

Three years later, erosion, ditches everywhere.

You know, no grass.

SCHANK: The Atlanta Housing Authority is taking their federal money and they're giving it to outside architect, outside contractor and the idea is that it's going to save some money, um, and while the upfront cost might be less, the Atlanta Housing Authority really ends up paying for it dearly in terms of poor construction, poor site design, so you see problems happening almost immediately.

GLOWER: I think this problem should be cleared up because it's causing a lot of inconvenience for a lot of tenants out here.

REPORTER: Is it the first time it's happened?

GLOWER: No, it isn't.

It happened in my apartment at least four times.

REPORTER: They say you don't miss your water until your well runs dry.

But East Lake Meadows residents say they wish they could miss their water.

Especially the sewage water which is now flooding their houses.

ALEXANDER: The infrastructure, what we learned after the construction, was completely inadequate.

The basic water lines, sewer lines, drainage lines were poorly done at best.

I think an argument could be made not only were they negligently done they were criminally negligently done.

KRUSE: As white residents left the city lost the tax money that they provided.

And so the city is home to more and more poor Americans, uh, who need more and more city services at the same time that the city is less and less able to afford them.

And so there's a need for public housing but there's not the capital behind it.

REPORTER: The angry tenants that have been picketing the Atlanta Housing Authority management offices have moved their demonstration into downtown Atlanta.

We're outside the AHA's main office here in the Hurt Building.

RESIDENT: We need better services period in Techwood and Clark Howell Homes.

We want this service and we are not playin'.

REPORTER: One of the things you find out very quickly in Perry Homes is that the people here put up with a lot, but their biggest complaint is the way this place looks.

And the say no matter what they do or no matter who they ask, no one will do anything about it.

RESIDENT: I've been here four years and the raggedy cabinets still torn up.

REPORTER: Your cabinet in the kitchen?

RESIDENT: And the floors need, uh, repairing.

RESIDENT 2: Roaches run through that, rats, you understand?

REPORTER: And you have tried to get them to fix this?

RESIDENT: How many times, how many times?

REPORTER: And what do they say?

RESIDENT: We'll get to it when we can.

HANNAH-JONES: Tenants can't get things fixed; the trash doesn't get picked up on time; the grass doesn't get cut anymore, and instead of saying, "“What's going on with the maintenance of the housing"” it suddenly becomes about the value and worth of the people who are living in there.

As if black and Latino people do not want decent housing, as if they do not want to keep up their housing... RESIDENT: Here the raw sewage.

HANNAH-JONES: But it's actually the government that's not keeping it up.

RESIDENT: See right here?

See how it stank?

I know you smell it.

We just got a dead project out here.

People just living here on borrowed time.

["“La Cova"” The New Mastersounds].

LONGINO: East Lake's location was off by itself far from downtown.

A lot of people didn't have cars... Um, so you would catch the bus or you would pay, ah, someone who had a car to take you where you needed to go, um, there weren't many cabs because they were afraid to come over into East Lake.

REPORTER: There are very few stores out here.

Most businessmen don't consider this a good place to open up shop, and that makes it hard for the people living here.

PRATTILLO: The separation of black neighborhoods and white neighborhoods means that businesses make discriminatory decisions about where to locate.

Things like grocery stores, day care centers, banks, health care centers, doctor's offices on and on, black neighborhoods get fewer of them, white neighborhoods get more of them.

It doesn't mean that black folks don't create many good things within their own neighborhoods.

MOORE: My dad used to have a rolling store, one of these big buses.

You know he'll load everything up on it from anything you need.

Toilet paper, washing powder, snacks, ch-chips like a store.

EL-AMIN: Penny candy, penny cookies, I mean, that we had our own candy store right there rolling, just rolling through the community.

Mr. Benny the vegetable guy?

No one knows where Mr. Benny got those vegetables, but one thing about him: They were always fresh.

the display was always nice, he was always on time.

You could've set your clock by Mr. Benny.

You know, he would come up and blow his horn, and everybody would run out to the truck and, "Okay, okay, okay one at a time!"

Ask you what you want: "Well Mr. Benny my mom says can she get such and such and such."

He would break out his composition book, write down what mama ordered, and say, "Tell your mama I'll see you next time, okay?"

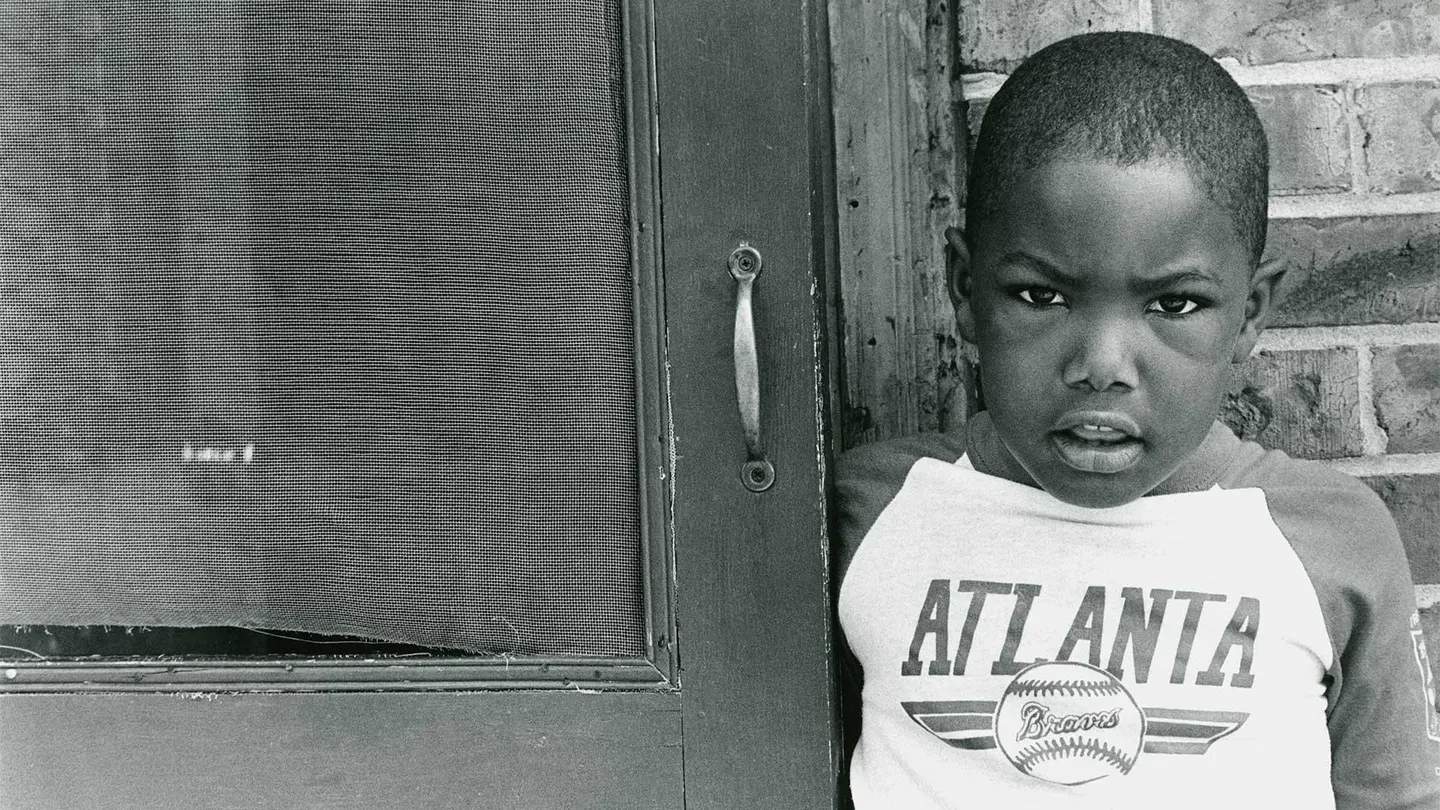

ANDERSON: East Lake Meadows.

It's like many government funded housing projects in this country.

Today over 5,000 people live here, most of them on welfare.

Many tenants recall the days when it was a nice place to live, but now they say it's run down, even dangerous.

PARKS: When you isolate people, like they did in East Lake, then it's almost like the people start preying on each other.

It's almost like we lose our humanity.

There's the drugs.

You get people cutting, fighting, killing, stealing.

ANDERSON: Kenny White says East Lake Meadows has a nickname: Vietnam.

That's because it's compared to a war zone.

WHITE: I see a whole lotta fighting, and cutting up and shooting.

ANDERSON: Young mothers fear for their children.

That's what Queen Wheeler says.

WHEELER: It's not really a good environment for them because it be too much shooting and fighting.

LONGINO: We knew to be in the house at the street lights, when the street lights come on.

And if you were caught outside after the street lights or weren't in the house that meant you were in big trouble because when the street lights come on things start happening and people wanted their kids safe in, in the home.

So that was basically our cue for curfew.

(siren) ELGIN: We got robbed once.

I just woke up one morning and my TV and my sister's TV was missing.

Somebody just walked in, they could've easily killed me, they just got my TV and left.

DAVIS: We call them quite often when we are being robbed, our senior citizens are being knocked down and pocket books took away from '‘em, our doors being broken into and our homes we'll call them and do you know what they ask us?

"“Where do you live?

"” We say, "“East Lake Meadows"” They say, "“well I'm sorry you have to call the police from Atlanta.

And then we call the police department from Atlanta, and it takes them an hour to get out here and sometimes they don't come at all.

CROWD: Right, right.

DAVIS: And so if they can't come to East Lake Meadows when we call them when we are in deadly need our lives are at stake.

What in the hell do they come out here for yesterday doing us like they did?

If they can't come out here to protect us why come out here to harass and scare us to death.

WOMAN: Right!

(gunshots) ELGIN: When there were gunshots you just want to see what happened.

One time I did actually witness a guy that was still there when I got there.

It was kind of, kind of weird and scary at the same time.

You know, because you're seeing them taking these last breaths and then I knew it was his last breath because you don't breathe like that.

you inhale all this air... (mimics inhaling).

Then there's this long pause.

and you sitting there looking, because you're a kid, you're curious.

and he exhales and it's like two more of those left I'm sure.

And then you see the last one and you're like, "“I think he's done.

"” It just hits home you see somebody die that you know... Or you hear about a friend the night before that got killed.

You shouldn't walk over dead bodies, people shouldn't shoot through your house.

That's not normal.

WILLIAMS: In disadvantaged neighborhoods, individuals have a higher level of any given stressful experience, and that changes how we function psychologically, how we feel emotionally, It has negative effects on our ability to adapt and cope with, with all of the adversities we face in life.

PARKS: At one moment everything would be ok and the next moment all hell would break loose.

we would witness people being shot.

Uh, rapes in the broad on daylight.

People were too afraid to report these things.

you could see a friend today and the next day they're dead.

These are the things that happened at, at, at East Lake.

BURSON: There was like a network of grandmothers, basically they ran everything around there.

It was like the grandmothers, then the aunts, and so on, but the grandmother was at the top.

The aunts would be like, her under bosses or whatever, but they kept everybody in line.

Not saying that there was like a total absence of men, but even with the men around the women ran it.

LIGHTFOOT: My mom cleaned homes for a lot of wealthy whites.

She helped with the kids, you know, she was like a nanny slash maid.

That was considered demeaning work.

But she didn't care.

She got up and did it for us.

Some people she worked for wanted to get rid of their piano to buy a new one.

So she wanted to buy the piano.

of course she did like she does everything, she paid a little bit on it, little bit on it until she paid for it and next thing we know, we got a piano in the living room.

I think we were the only people in the projects with a piano.

ELGIN: The first song I learned was, '‘I'll Take You There' by the Staple Singers.

Seriously.

(sings melody).

♪ WOMAN: I know a place ain't nobody cryin ♪♪ ELGIN: Then the gospel part would come in, and I'd just... (sings melody) And I loved it and I played that song every day.

♪ WOMAN: Aint no smiling faces.

♪ ♪ CHOIR: I'll take you there.

♪ ♪ WOMAN: Happy y'all.

♪ ♪ CHOIR: I'll take you there.

♪ ELGIN: Since the walls are so thin in the projects, the lady next door would play music for like, you know they'd have these drinking parties.

You know, drinking, dancing, doing whatever.

she would put a stack of records on the 45 and they would all drop down.

But that last record would keep playing.

Often times the record would play fifteen times.

But that's what I needed I would just play along with the record.

If I didn't get it right the first time I would get it right that fifteenth time.

And so, I did that everyday almost.

And that was my teacher.

So I learned how to play a lot of songs off her music.

♪ WOMAN: Ah, ah, ah.

Oh, ah, ah, ah ♪ ♪ I know a place, y'all.

♪ ♪ CHOIR: I'll take you there.

♪ BARBARA: When you're poor you make your own fun and that's what we did.

The kids and everything, it's just like a big party and that's the best thing I remember.

People could still get together in spite of them being really poor.

They knew how to get together and still have a good time and enjoy life.

♪ WOMAN: Oh.

♪ ♪ CHOIR: I'll take you there.

♪ ♪ WOMAN: Oh, oh, oh.

♪ PARKS: Even in poverty, there's always light.

And I think that's most of our history as black folks.

There's always that beacon of light through there.

So, we used to joke and we would look for happiness wherever we could find it.

♪ WOMAN: Gotta let me, let me take you, take you ♪ ♪ CHOIR: I'll take you there ♪ ♪ WOMAN: Take you over there.

♪ ♪ CHOIR: I'll take you there ♪ ["“Something You Got"” Wilson Pickett].

♪ PICKETT: Something you got ♪♪ LIGHTFOOT: What I saw from my mom was I saw determination.

I don't why she chose me, but one morning, she got me up and she said, "I'm gonna buy me a house."

She said, "I know nobody thinks I'm gonna get one.

I'm gonna move out of the projects."

And she got me, she took me to the bank downtown Atlanta.

We caught the bus and I went down to the bank with her and she said, "I have a bank account.

This is my bank book."

She said, "I'mma put whatever I can in this account until I get enough money to buy me a house."

And I never forget she put $5 in and I said to myself, "That's gonna take a while.

You know, that's gonna take quite a while,"” you know?

She would come home from work, she would give me 25, 35, 10 dollars, 15 dollars, and what I got a chance to see is as the years progressed I looked and I said, "Wow.

Mama started off with $5 and now she got $2000."

You know?

So, I saw what determination could get you.

ELGIN: I was in the eleventh grade when she finally saved enough money and bought a house on Tupelo Street.

And I had my own room I was so happy when she moved.

I couldn't wait to tell everybody, I just moved out of Little Vietnam.

If you came out of that unscathed you, you were lucky, but do you know what's funny?

We moved but I came back to East Lake Meadows every day.

I couldn't leave.

["“My Life"” Mary J. Blige].

ALLEN: I was born in Ohio.

My mom experienced, um... A really bad situation with, in, in a relationship she was in my mom was brutally beaten by a man who she was with and he tried to kill her.

She wanted to just get as far away as she could.

So she moved to Georgia and took all of the kids with her.

We stayed in the car, the four of us just living out of the back of the car until we was placed in a shelter.

You stay at a shelter for '‘x' amount of time until they place you and that's how we were placed in East Lake Meadows.

HARRISON: My mother and father separated.

When I was 14 years old my dad moved out to East Lake Meadows.

I told my dad that I don't want to stay with mama no more because she's too strict, she won't let me live there.

He said, "Well, come and stay with me."

When I got there, oh man.

I mean, I was exposed to a lot of things that I never thought in life that I would be exposed to at a young age.

["“Party Groove"” ShowBiz & A.G].

♪ CHUCK D: Hear the drummer get wicked.

♪ CRITTENDON: It was a whole different environment of living for me, me coming out of foster home to now I'm in the most ruthless projects in Atlanta, know what I'm saying.

It don't matter how much my mama cleaned because we were clean people, it was the roaches.

The roaches would not stop coming, you know.

You lay your bowl of cereal down on the table, they parachuting from the ceiling.

So I would put a bowl of cereal down and I come right back, right quick, and man there's a roach in my cereal.

What you going to do?

You going to throw that whole bowl of cereal away or you going to flick that roach up out your cereal and eat it?

That's how, that's how hard it was in the '‘jects, man.

♪ CHUCK D: Hear the drummer get wicked.

♪ ♪ Wicked, wicked, wicked, wicked ♪ MOORE: I was 17 when I had my first son and I was one of the proudest dad you probably would ever meet.

And raising my kids in there was tough.

You had to make ends meet.

you bringing kids in the world, they got to eat.

I started selling drugs because it was in the family.

At the time my brother did it, my dad did it, that was our way of surviving, you know, because it was hard to get a job.

For a black man anyways.

CRITTENDON: Basically when you open your refrigerator you ain't got nothing to eat, you know, you gotta put some food on the table.

So we turned to pumping gas, hustling I asked some people could we pump gas for a quarter.

That was just a sales pitch because we'd end up getting a dollars or whatever because people were respecting that you was from the projects and that you was trying to make an honest living.

ALLEN: If you were a young man in need of money, you would go and you'd pump people's gas and they'd give tips or whatever.

But then that wasn't enough money anymore.

["“Night Drums"” African Drum Masters].

REPORTER: Across the country, crack has already surfaced in at least 19 of the nation's largest cities.

Some addicts say crack's been available in backstreet Atlanta for over a year and a half.

CRITTENDON: It happened real fast.

Soon as crack hit, man, it hit like a wave.

REPORTER: Crack is the drug dealers dream.

For quick marketing the convenient new coke, like a fast food.

CRITTENDON: That's when the money started coming in.

It was fast it was very fast.

you'd make a $1000 in less than an hour, that's fast.

You had drug dealers out there, they're throwing up money, you know what I'm saying?

People that didn't have cars got cars.

HARRISON: I mean, I was like, "Yeah man, I'm going to end up being like that one day, man.

I know it, man.

I can be like Black, you know, or Red."

'‘Cause they had these nicknames.

I started really learning the game.

I started really selling.

At the age 14, too.

I mean, I was like, "Oh man, this is it."

Everybody heard about Lil' Willie man.

"Lil' Willie be making that money, man.

CRITTENDON: I just started being like a lookout boy.

My job was just to alerts other people that was out there serving the drugs when the police were coming up the street.

So I would get out of school, do my homework, again I'm heading to them.

You know, trying to make some money for the day.

I was looking at it as being a meal a day for my family.

ALLEN: I mean, you'd have people walking around high, cracked out, looking for some more crack... People who, were perfectly normal one day, the next day they're just not functioning.

I mean, they just walking, trying to find some crack.

And you can tell, because, you know, they had something to sell.

Something to sell, always something to sell.

HARRISON: Everybody used to party, hang in the streets, just drink beer or whatever.

Man, we was okay, it was like we was close.

But when crack cocaine hit, we became extremely divided.

There was no more parties.

It was like a ghost town.

I met a guy who was sitting there smoking, and then I asked him what he was smoking, and one thing led to another.

I said, "Let me hit it.

Let me try that."

I tried it, so it was crack cocaine and weed.

So, hey, that's all I needed right then.

I didn't think about no food, no nothing.

But when I started doing those drugs man, it just went down.

OFFICER: You have the right to remain silent.

Anything you say can and will be used against you in the court of law.

MAN: Right, right.

CHUNG: In Atlanta, there is a housing project where drugs are rampant.

There's so much gun fire the post office sometimes refuses to deliver the mail.

REPORTER: Yet another child, the second in two years, has died at East Lake Meadows, a victim of the violence associated with the sale and use of illegal drugs.

Police say about 200 gang members have been operating in the area.

Gangs go by such names as Warriors, Creepers, and Down By Law.

RESIDENT: I have saw I think about three guys get killed out here behind drugs.

MARSHALL: It was maybe like three or four times a week, you know have shotguns shooting.

I would get my kids and go in the bathroom, or if I didn't have time to do that, we would just lay on the floor.

Sometimes it might be 20, 30 shots, sometimes it be two or three, but when it was over with, you know, we got up and kept living.

HOBSON: You see this overwhelming violence.

robberies, assaults, murders, you had law abiding citizens, who were just down and out on their luck, living in these housing projects, that were being held hostage by the corner boys and then their own communities are being decimated through the use of crack cocaine.

REPORTER: There has been talk of building a fence around the project, an effort to keep crime out.

But tenant association president Eva Davis says that's not what the community needs.

DAVIS: We want a community center, we want some social services programs out there, we want a place for our children to be able to go and play, we need a place for afterschool activities for our children.

We need that more than we do a fence.

HEATH: My mom would call the police on you in a heartbeat.

And she would run you, out from in front her place, or even off that street.

She was a gangster when it come to drugs.

LONGINO: If you're telling someone that they can't sell drugs and that's their revenue, that was a threat.

And it even got to a point where when she didn't back down they fire bombed her apartment.

And we ran out, apartment fully engulfed...

But she refused to move.

She did not want them to move her.

DAVIS: And I hope to Lord that the police department... LONGINO: It was time for a meetin' and she went through the community and she was on the bullhorn announcing we're having a meeting because you didn't kill me.

I just never saw her cry, sweat, which it still amazes me to this day.

I just, I just never saw her break.

OFFICER: Show me your hands!

Get on your knees, get on your knees!

BELL: I plan to keep some police presence in, uh, East Lake Meadows.

REPORTER: Chief Bell noted the Red Dog anti-drug unit continues to work public housing projects with a great deal of success.

He said starting today he plans to put crime prevention resources in East Lake Meadows.

BLACKMON: While there's almost no money from any source making its way to an East Lake Meadows to address the human suffering that is there or to open up meaningful channels for people to make their way out of the situation, there is now an avalanche of money going to law enforcements agencies and the people who believe it's their job to police the behavior in these places and, contain what they view as a kind of evil contagion.

HARRISON: We used to go into abandoned apartments and just sit and smoke crack cocaine, or sometimes, we'd just sit there.

I used to spend the night there.

Only thing you think about is just getting high.

You didn't think about your family, your friends.

You didn't care about no one or what anybody else thought.

They used to call me a junkie.

"Man, Lil' Willie, you done became a junkie, man."

When you got on crack cocaine you was ashamed.

You became ashamed.

So, what I used to do, I used to run.

I used to run and cry a lot.

CRITTENDON: I got caught up when I was 14, 15.

We was stealing cars and hanging out late, We were terrorizing the city we was robbing every day.

That's what got me in prison.

HARRISON: I went to prison in November of 1989.

I was 17 years old.

I was charged for murder and armed robbery and I was sentenced to life plus 20 years in prison.

At that moment when I pulled the gun out, I was high, I was on drugs at that moment and I was really, really angry.

I wasn't angry at who I actually killed but when that moment happened I had no feeling, no remorse, nothing.

ALLEN: My mom was strung-out on drugs.

You know, we had people that were doctors, nurses, good jobs, construction workers and lawyers, come to her house to get high.

And it just felt like, "“Aw, no.

We were just having so much fun.

"” And then it's, "“Okay, go upstairs and when my company leaves, you can come back down.

"” I just got tired of it and it hurt, it really did.

I cried in my room.

So I just, I had dolls upstairs in my room and I would play with my dolls, and play school with my dolls, and I had a full class session going upstairs.

I would teach them and read them books as if though they were real live people.

And I enjoyed it.

I just didn't know from day to day what was going to become of me in the future.

I love my mom and I wanted her to be there more for me.

And the times where she wasn't doing drugs, we spent good quality time together.

Like sitting by the window, talking about the most simplest thing, but it was so big to me.

She said, "“Now, I'm going to tell you some things.

It might not come out right, but just listen to it.

"“Just listen to what I tell you and don't pay attention to what I do.

and I won't steer you wrong.

"” And she didn't.

She did the best she could do.

She did the best she could do with what she had.

["“Pushed Back"” Doug Wamble].

BARSH: I moved into East Lake Meadows in, around, '92, because it was taking all of my money just to pay the rent.

When you can't buy a simple thing like an ice cream cone unless you take some of your bill money, that's not a good feeling.

I was determined that no matter how long it took, I'm coming off this welfare, I wanted to be an X-ray tech, so I enrolled myself in school at Grady School of Radiologic Technology and it was going well but when I received my financial aid, they were calculating the grant money as though it's my income.

so my rent went up, the food stamps went down.

It just caused everything to start crumbling.

It was like you take one step forward and you get pushed back five steps.

PHYLLIS: Lupita!

WOODS: We had a two bedroom, small little unit, uh, it was me, my mom, my two sisters, and my littlest, youngest brother was born there, my mom worked two jobs, and she was a security guard, she was also the hair stylist in the neighborhood.

PHYLLIS: What's your name?

LUPE: Lupe.

PHYLLIS: What's your name?

MARTY: Her name white girl.

PHYLLIS: What's your name?

WOODS: My dad is Mexican so people were always trying to fight us because they were like, "Oh, those are mixed race kids, they probably have a little more money."

Even though we're from the same place.

PHYLLIS: This is a quiet little girl.

She's the head of her class.

She's smart and she's beautiful.

WOODS: They would just pick on us.

There was drunks, there were crackheads around it was like a war zone.

MUHAMMAD: It is heartbreaking to be poor.

me and my husband was always having financial difficulties.

I had three daughters and they depended on us both to make sure that they had they housing and shelter.

And I didn't want them to ever know what it felt like to not ever have a roof over their head.

The day I moved in, oh, wow.

Sorry...

Cause that was...

The day we moved in was okay.

It was a pretty day, children were happy, um and two maybe hours later, we heard some gunshots and found out that someone had got killed right up under the steps where we had just moved into.

And it was rough trying to, um...

Trying to help them understand what had happened and that we would be okay.

["“Hard Times"” Run DMC].

CHANCELLOR: Cabrini Green is not a color.

It's a high rise crime wave.

REPORTER: There's little hope saving the Columbus Homes.

Deterioration there has just gone too far.

The Newark Housing Authority... REPORTER 2: In the next week, AHA commissioners will begin examining what few options they have for offsetting the cut in federal dollars, but at this point, those options are slim.

JENNINGS: Public housing projects in Chicago are the worst in the country.

Riddled by drugs, overrun by gangs.

REPORTER: The elevators in the eight-story building don't work.

Neither do the incinerators.

♪ DMC: Hard times.

♪ ♪ Spreading just like the flu.

♪ ♪ Watch out homeboy don't let it catch you.

♪ REPORTER: Public Housing projects.

They can be eye sores to those who live near them, and nightmares for those who live in them.

HANNAH-JONES: The media plays a huge role in this narrative about public housing REAGAN: No one in the United States knows how many people are on welfare.

HANNAH-JONES: The image of the "Welfare Queen," which is popularized by Ronald Reagan, is, ah, kind of set in stone by the media.

The media picks up on this; the media picks up on what we now know to be a debunked myth, of the crack baby, um, the media picks up on this idea of the super predator.

Of all of these, terrible societal problems that are coming out of public housing and public housing becomes the image for all of that.

VALE: It becomes a way for the public to generalize from the worst case scenarios, the most violent places to the entire program ignoring the fact that, that this is some projects in some cities and that most of public housing, ah, across three thousand different housing authorities in the country, ah, doesn't have that degree of problem.

♪ RUN: All day I have to work at my peak ♪ ♪ Because we need that dollar ♪ HANNAH-JONES: We never saw, um, more than one image of public housing.

and it's not to downplay how difficult it could be in that environment.

But what you didn't see was the communities that people had forged for themselves.

The long bonds that people had across generations with each other.

I don't think we ever gave enough credit to what that experience was really like for people who worked very hard, um, to build a place for themselves that was safe, who had relationships and who had people who they could depend on when there was no one else who was going to be there.

♪ RUN-DMC: Hard Times.

♪ SMALL: It's a myth that people aren't trying.

You get really high quality schools in a low income neighborhood and you're gonna see kids one after the other saying, "“I wanna go to college.

I want a good education."

This idea that people as a general statement wanna stay in their conditions because they wanna be wards of the state...

It's just not consistent with the evidence.

♪ RUN-DMC: I'm gonna keep on fighting 'til my very last breath.

♪ DOLE: Let's take public housing for instance.

Public housing is one of the last bastions of socialism in the world.

Imagine the United States government owns housing where an entire class of citizens permanently live.

We are the landlords of misery.

GINGRICH: Let's talk about what the welfare state has created.

We end up with the drug-addicted underclass with no sense of humanity, no sense of civilization, and no sense of the rules of life in which human beings respect each other.

CHABOT: We must reduce illegitimacy, require work, and save tax payers money.

CLINTON: Perhaps the most important legislative issue Congress will take up this year is welfare reform.

And I strongly believe we have to end the welfare system as we know it.

COBB: In the 1990s we saw the culmination, of kind of 20 years of increasing resentment and antipathy, uh, toward, uh, poor people toward public services, toward, uh, African-Americans to people of color.

it was reflected in things like welfare reform, the idea that the public coffers had to, stop being fleeced by these undeserving people.

PRATTILLO: We malign entitlements because we are often blind to the ones that we receive and have helped us so much, and we often see the beneficiaries of those entitlements or the beneficiaries of any kinds of benefits, as weak, as dependent.

We spend way more on supporting people who buy multimillion dollar houses and write off the mortgage interest from those houses, than we do on subsidizing housing for poor people.

VALE: So the backlash of this was both against the poor people who would be blamed for the chaos of their conditions a blame that paid no attention to the withdrawal of funds needed to maintain these places, but also, ah, a sense that maybe the government wasn't any good at doing this to begin with.

Enough already.

It's not housing the right people.

It's the wrong kind of building.

It's the wrong kind of investment.

We should start over.

(crowd exclaims) (explosions) HANNAH-JONES: There's these larger forces that they want to start bringing white people back into the city and middle class people back into the city.

They want to start to reclaim these areas.

So you start to see a, um, a lot of policies to, to implode and bring these public housing structures down under the guise of new federal programs that are going to be mixed income.

CISNEROS: When I became the Secretary in 1993, the Atlanta Housing Authority was one of the more troubled in the country.

Our vision is to replace them with lower scale town houses, smaller in density with physical security built in a way that brings dignity to the people in the neighborhood.

CISNEROS: You had the idea that we had these concentrations of poverty that we could only break up by creating mixed-income settings, which meant some allowance for higher incomes in the mix.

GLOVER: What we're trying to do is deal with the issues in a substantive and comprehensive way.

VALE: When Renee Glover comes on board, ah, initially as, ah, a board member then chair and then CEO of the Housing Authority by 1994, uh, she had an enormous task and an enormous opportunity.

GLOVER: I'd like to tell you that within 18 months we have solved all the problems.

But the fact of the matter is, is that, when you inherit something that has been mismanaged for 20 years it takes a while to build the capacity... Atlanta had the highest violent crime rate in America.

Atlanta had more public housing per capita than any other city in America.

Atlanta's public schools were failing so things were really dire.

I didn't think that just because people were receiving a subsidy that they had to live in these horrible conditions.

REPORTER: These days, the head of the Atlanta Housing Authority is heralding the beginning of a new era.

SCHANK: Up until that point the idea was, "“How can we rehab it?

What social programs can we put into place?

What modernization things can we do to the grounds, to the physical buildings.

"” But Glover says it might be time for this all to go.

GLOVER: So Phase one is all of Techwood... REPORTER: the housing project will be torn down and completely rebuilt as a mixed-income development.

The first phase should be complete by the time the Olympics get underway in 1996.

["“The People That They Were"” Doug Wamble].

BLACKMON: When word of the of this idea of redeveloping East Lake Meadows tearing it down, rebuilding it, first arrived I think the tenants' first reaction was "“Well this will never happen just like nothing else has ever happened.

"” But if you wanna do anything out here, you're gonna come and talk to us about it first.

Nobody's gonna do this to us.

COUSINS: We adopted the East Lake Community and this specific housing project which was the center, or the primary problem in the community.

GLOVER: Tom Cousins had expressed interest in wanting to do something out at East Lake.

He had purchased recently the Bobby Jones Golf Course across the street.

And because of the violent crimes that were going on at East Lake Meadows, it was very difficult to get anything going cause there was literally shooting, ah, that was going on, on the property.

BLACKMON: I think that Tom Cousins looked at this situation and saw a kind of you know win-win-win.

"We should make a big bet."

Let's go in and put a lot of resources into one thing that can make a big difference and that would be to turn around this terrible housing project.

DAVIS: My Lord, the shower got holes all in it up in there.

It don't make no sense.

It's ridiculous.

GLOVER: For East Lake Meadows it had everything to do with Eva Davis, when we started the conversation I think Ms. Davis was skeptical about whether or not, ah, a mixed-income community could work.

MUHAMMAD: Miss Davis felt that they was trying to steal that land back.

and expand the whole golf course all the way through.

And they kept trying to tell to us that, "“No, that wasn't going to happen.

"” But that suspicion was always in the back of everybody's head.

NAUGHTON: That's a really scary proposition if the only thing standing between you and homelessness is the public housing unit that you occupy.

And for families who have not been well served by the school system, by the housing authority, by virtually every institution that was supposed to support them, that was a major act of trust for people to say, "“Okay, I would be willing to leave this community on the promise that you will let me back.

"” REPORTER: You don't own this.

So how can you tell them what to do with something that you don't own?

DAVIS: Well, they think we are dumb, they think we are stupid, erratic, and crazy.

They don't even give the residents of this development, credit for even having common sense in which we were born with.

BLACKMON: They didn't own the property.

They didn't own their apartments.

They had no legal power of any kind.

And the Atlanta Housing Authority could have just walked in one day and said everybody out tomorrow and brought in bulldozers the day after that.

So Eva Davis had no power at all except that if you were a politician who needed votes there she could mess things up for you.

But also Eva Davis could just make it painful for you to try to do anything in this environment.

STUDENT: Will the people who live here get to come back?

GLOVER: Well that is a very insightful question.

And that's a question we have been spending a lot of time with the planning committee.

there are a number of residents who live in the East Lake Meadows community who are representing all of you and all of the other families who live at East Lake Meadows and one of the questions that we have talked about is the right of the families to return to the community.

BARSH: Techwood was the first redevelopment and it was very well-known that only about maybe 25% or 30% of the, the new apartments were available for public housing residents.

a lot of the residents was not able to come back to Techwood.

RESIDENT: All they want to do is to get us out regardless of where we go.

They don't care.

As long as we get out their buildings.

WOMAN 2: I think that they are going to move another class of people into the inner city and move us back to the outer city if they can.

NAUGHTON: The planning process was really about making those decisions: how many apartments are we gonna be able to build back on site?

What would the income mix be?

Ms. Davis felt very strongly she wanted it 50% public housing assisted and 50% market rate.

ALEXANDER: The debates were very intense about who should be allowed to live in the community.

The Residents' Association had as their image the people that they were.

They wanted to exclude the violent ones.

The Housing Authority had an image of a higher income class of tenants.

So we began to see much stricter lease enforcement by the Housing Authority.

WOODS: The biggest memory, to me is when everybody started getting evicted.

And a lot of people's stuff being thrown in front.

And everyone that was left would flock there and try to take all their stuff, there was always somebody that was there trying to fight people away to keep their stuff because people were coming from all angles to try to get stuff.

All the druggies would come, try to sell that stuff.

MUHAMMAD: It took tolls on a lot of us and especially Miss Davis out of all people, it took a toll on her.

But we did have to eventually come down to saying, "“Okay, are we going to go with this plan or we not going to go with this plan?

"” BLACKMON: So this finally comes together.

Eva Davis, ah, is, is finally reconciled to this for a variety of reasons.

I think that Eva had actually begun to come to terms with the fact that she was not gonna be alive forever.

But, I remember sitting with her and talking about this, "How did you make this turn that you've made?

"” Um, and, and she said something to the effect of that, "“Something is gonna happen out of this and so I think this is what we oughta do.

"” NAUGHTON: Even though it wasn't required under HUD regulations we all felt it was important for the community to vote on this change because it was such a monumental change.

And so Ms. Davis, um, took it to the Resident Association for a vote.

BLACKMON: And so it then comes to this meeting in the community center there out at East Lake Meadows...

It's a tense room, it's a tiny little room without air conditioning and people are packed into it, you know.

It's a broken down old community center, ugly, squat building.

Police outside.

HEATH: Three or four of the tenants gathered a group of people together and say, "Eva Davis lyin'!

She's gone get, get these people, let them buy this out from under you, you ain't gon' have nowhere to go."

DAVIS: They was poisoning residents mind telling them once they get you out of there you ain't coming back.

I said "“oh yeah, you're coming back if you want to come back if you done lived right in the past..."” MUHAMMAD: It was really intense because a lot of people spoke their opinion, a lot of people was saying that actually we was sellouts, that... Miss Davis was being offered this nice home.

it was very heated.

LONGINO: My grandmother jumped up, um, and you know she said, you know, "“Wait a minute!

"” Are you sayin' you don't want better schools or a better place to live for your kids?

Aren't you tired of duckin' bullets?

you can't really want another lifetime of what we're already in... NAUGHTON: Finally Ms. Davis called the question and people voted overwhelmingly in favor of tearing East Lake Meadows down, relocating, rebuilding in the model that we had been negotiating for the last year and a half.

(cheers).

(cheers).

REPORTER: So, what do you think seeing all this going on?

SHANNON: It's great.

I thought it would never happen.

It's great.

REPORTER: Alright, A little sadness seeing any of this go?

SHANNON: No, no, no sadness, no!

♪ BOTH: East Lake!

East Lake!

♪ ♪ You better get ready to move, we're coming to town.

♪ ♪ East Lake, East Lake!

♪ ♪ Better get ready to move, where you gonna go?

♪ ♪ When they tear east lake down.

♪ WOODS: Video club was set up through school.

They gave us a video camera and a microphone, some journals, we would rap, and sing.

♪ CHILD: We're coming to town.

♪ WOODS: We'd just be living our little lives through the little camera that we had.

MARTY: This is where they are tearing down all of the houses.

I am kind of sad because I have lived here all my life.

That is where people still live.

MARTY: These are the new apartments.

LUPE: Hi this is Lupe Barnes we're showing about the houses.

We're going inside.

REALTOR: Ya'll used to live in East Lake Meadows?

GIRLS: Mmm-hmm.

REALTOR: So you kinda want to see, you know, what everything looks like?

PHYLLIS: Yeah.

REALTOR: This is a four bedroom and down here you have half a bathroom.

This is a dining room area, okay?

And I'm going to show you guys out this door and you kind of get you a little picture of the golf course there.

Is anybody, uh, parents, uh, coming back over here to stay or, just, no?

ALLEN: When we saw them tearing the apartments down one by one, they were promising that they would move people out per building move them somewhere while they renovate the building, and bring them back.

But we were seeing buildings being, just torn down and people dispersing.

We just saw everybody around us gone.

We didn't want to be the only ones in the building so we moved out and that was that for East Lake Meadows.

We didn't, didn't go back.

♪ ♪ ALEXANDER: A substantial number of them simply wanted to get away.

The other half, or perhaps more, wanted ultimately to be able to come back.

they wanted the right to return.

Every month some tenants would voluntarily leave; some tenants were being evicted.

So the total pool of affected families was declining.

By the summer of '98 we probably had less than seventy families on site.

MUHAMMAD: My main decision that I made to actually take the Section 8 voucher and move from East Lake was my girls had got involved with some young boys over there that actually was messing around with drugs and dealing drugs.

I did not want them to be involved with that.

The actual getting the voucher that was easy.

The process of looking for a house and trying to find the area you wanted to live in was the hardest part because everybody didn't accept Section 8 vouchers.

And a lot of people, when they found out that you moving from a housing project, that was another stigma they had on people too.

But it just so happened I found a, um, landlord that was in Gwinnett County that was willing to take the voucher.

ROSENSTEIN: In most places, if you have a Section 8 voucher that's helping you to pay the rent, a landlord is permitted to refuse to rent an apartment to you.

the result is that most apartments that are available to rent for Section 8 voucher holders are in already segregated communities.

HANNAH-JONES: So these vouchers which were supposed to get poor people out of poor neighborhoods, end up keeping them in poor neighborhoods.

And the only place that they're able to use the vouchers are in the same crummy neighborhoods that the housing projects were in that they were trying to escape.

GLOVER: You'll often hear the critics say about the Section 8 Program that families were moving from one, ah, low income neighborhood to another.

And if you put it in the context of what was going on with racial segregation, well of course that's where families were moving.

One that was the only place where they could move.

But at least the poverty was not as concentrated as it was in the public housing.

VALE: Renee Glover is supremely confident that this was the right way to go.

And she always is careful to frame the situation as this is a terrible place, there was no community there at all, good riddance, the question is are there important losses to moving away?

And how dependent are people in good ways on the community that they once enjoyed?

the capacity to provide support networks, the capacity to have childcare from a family member the proximity to some kind of job should we be completely dismissive of those things?

PATTILLO: In many cities, what we have done, is move the conditions somewhere else, and in many respects it's about just moving people around so that we don't have to see the deplorable conditions.

LUPE: This is our house.

And as you can see the ribbons... WOODS: I didn't want to end up like the other people that didn't have homes and were living on the street, or that got their stuff thrown out.

So, I was happy about moving.

We had a voucher.

We ended up moving to Candler Road, to a little green house out there.

It was a little street with houses on it and we had our own space we got to get away from.

There was still people with their loud music and hanging outside drunk and stuff like that, but of course we were a lot more happy because it was our little house.

CRITTENDON: In prison I had seen the newspapers word on the street, they tearing down a lot of the projects in Atlanta and we was one of the first ones to go.

I got out, 2001, February the 16th it was no more Meadows.

WOODS: When they finally got it up, my mom took us down there and we all went down there as a family.

And we just walked around and looked at what our neighborhood had turned into.

It was where we grew up at, So we went back and we just looked around and, that was that.

They were still doing construction on some parts and that was the last time I went back.

DAVIS: They tore down hell, and they built heaven.

And now we are living in paradise.

LONGINO: She got what she wanted and as long as she was happy I was happy.

She didn't wanna live anywhere else.

She didn't have a desire to do anything.

She ate, slept and breathed East Lake.

It was her world.

EL-AMIN: I didn't know she had ovarian cancer until later on My grandmother said that she didn't want to go to a hospice, if she was going to pass away, she was going to pass away in her home.

I can remember it was a Monday morning I was on the way to work my uncle called me and said, "She was gone."

She died at home.

I miss her a lot.

I miss talking to her, hearing her advice, because she gave a lot of advice.

I really miss her.

NAUGHTON: The Villages of East Lake will always have 542 mixed-income apartments including 271 that are reserved for low-income families.

EL-AMIN: We have a bank now, we never had a bank.

We have a grocery store, Publix, we never had a grocery store.

It's safe.

It's safe.

What community wouldn't want to have a security company?

Gated community.

You have to have rules.

If you don't have rules, it'll go back to what it used to be.

BOSTON: The uniqueness of what the Atlanta Housing Authority did and also the Cousin Family Foundation is that they started from the standpoint of trying to create an environment that would allow families to be more upwardly mobile.

They have a charter school there.

A new YMCA.

Early childhood development centers, daycare.

They have after school programs.

At East Lake they can learn how to play golf.

Some of the original families moved back, but that was roughly only about 15% of the families.

ALEXANDER: East Lake Meadows was occupied by the poorest people who had the greatest needs and the fewest support mechanisms.

Many of them were disqualified from coming back.

Stricter screening requirements were in place.

The goal of the Housing Authority in the new community was to have a higher income class of residents than lived in the Meadows.

A handful of families ultimately got back in to the Villages.

And most of them could not afford to remain there.

BLACKMON: A clear benefit was for that subset of the original residents who were able to come back they did come back to, ah, a certainly much nicer existence than they'd had before and one without the crime and, and that is the case.

There's no doubt about that.

ZAKEYAH: I go to Drew Charter and we have an elementary school, and a high school, and a middle school.

And it's very popular, let's just say that.

MS. TAMBER: Arms up.

Here we go!

Let's go!

Yeah.

JAMILAH: There's always a story with my mom about how her school career was different from mine, how they didn't learn the same things that we did, so it's really interesting, um, how different things were then then now.

MS. TAMBER: Good and stop.

TEACHER: Monday, we are going to review and I'll give you the study guide.

And then the test will be on Friday.

EL-AMIN: They want to go to college and Jamilah, she was saying that she wanted to move to New York at one point, so they have a mind of their own and I want them to stick with it and don't deter away from it.

So they, their dreams are when they finish Drew, they're going off to school.

That's it.

NAUGHTON: The surrounding neighborhood, the single-family neighborhood really has changed dramatically.

It has become much wealthier.

Back in 1995 the average sales price of a house in the East Lake neighborhood was about $45,000 if you could find a buyer.

Today, the average sales price of a home in the community is about $260,000 ALEXANDER: It is tough to create a brand new community in an area that has developed a very tough reputation.

So it takes courage to do it in the Villages.

The danger is forgetting for whom it is being built.

WOMAN: Don't have that on now.

MOM: It ain't on.

WOMAN: It is I see the light.

You think I'm crazy, man.

(inaudible).

ALEXANDER: We lost sight of the population, the individuals, the families that lived there when the demolition began.

It has created a stronger community but it has also created a community where it's tough to live if you're making minimum wage or less I don't wanna be critical of the Villages as a success in its own right.

What I am quite critical of is the fashioning of housing policies where we no longer serve those who are most in need.

GOETZ: If you're only looking at the place, then there's really no denying that it is amazingly different And that it works for the people who live there in ways that are almost unimaginable given the previous kinds of, of conditions that existed.

So as place-based redevelopment, the model is really quite good if, however, one is interested in the welfare of the original residents, then the model was insufficiently attentive to their needs.

where they ended up and the impact of this on them.

Our record nationally in terms of getting original families back on site is ridiculously bad.

We made better places, but we by and large didn't make better places for the people who originally lived there.

BURSON: When they tore down East Lake Meadow they displaced a lot of people, but it needed to be torn down.

It was dilapidated, crime filled, just run through, so it was time, but the way they did things after they demolished it.

They promised families that they would be able to come back in.

life would be better.

It didn't happen that way.

Some people attempted to get back in only to be told, well we caught your grandson over in a neighborhood seven, eight blocks away and he was selling drugs, so he can't come back and you can't come back.

I mean if you gonna take something away from them and they're innocent, give it back.